Today, I’m starting a short series about basic principles of composition that show up in the visual arts. I started thinking about these principles after seeing Kat's portfolio. The first installment is on the form used most often in classicism, be it painting, sculpture, or architecture. You'll find it elsewhere too, just in case you were wondering.

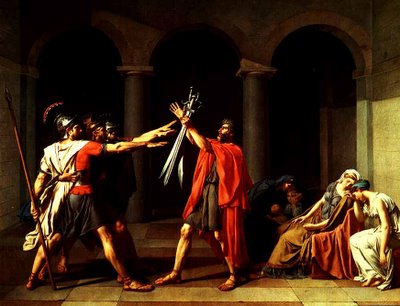

This is Oath of the Horatii, from 1784 by Jaques-Louis David, one of the foremost painters of the French Neo-Classical academic style. What you see is a dramatic scene, the moment when the Horatii brothers enter into an oath to fight. Opposite them, the women are already weeping for the loss of their husbands. For all the action going on in the depiction, all the dramatic light, all the force of gesture, and so on, the piece remains entirely static.

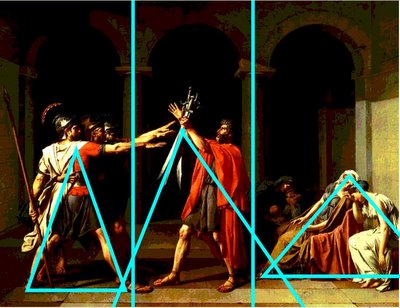

Why is that? Well, here are some lines that I’ve drawn in to illustrate the compositional devices that are specifically designed to give stability and “weight” to the image.

The background is BORING, and deliberately so. No one’s attention is getting lost back there. It’s black and uninteresting, pushing the eye back to the people in the foreground. The three arches in the dark divide the image in to three sections, and each of those three sections has a stable, bottom-weighted triangle within it. The center triangle is done most cleverly, with the swords and forearm grasping them continuing the perspective lines of the floor. The central figure’s legs are nearly parallel to these lines as well, which reinforces the viewer’s perception of his stability.

Static composition is pretty easy to achieve with triangles like this, because it is pretty hard to throw a pyramid or a tri-pod off balance. The drawback to composition of this style is that it isn’t very exciting. The images looks lifeless despite the phenomenally lifelike rendering, because real life isn’t that balanced.

Stay tuned for dynamic composition tomorrow.

7 comments:

Doesn't it seem to be the case in many dramatic renderings in the baroque era? Could it be that this composition had the purpose of reminding the viewer of the illusion of reality as opposed to reality itself? or is it the supremacy of form over emotion?

Hey Fouad, I just checked our your Lebanese Dream--liked it a lot.

The intent and desire of Baroque artists differed quite a bit from their Neo-Classical counterparts. I'm not too great with Baroque, but your description of the "illusion of reality" seems to best fit the Mannerist style that came in the wake of the Italian Renaissance.

There is a lot in French Neo-Classicism that seems to subvert life to art, or wish to make life as art-like as possible.

neo-classicism in art coincides with regular classicism in music (musical neoclassicism refers to the early 20th C). i'm talking about the great symmetrist mozart. the oath of the horatii is actually in the music history text i use in my class to show the kind of balance classical composers preferred. if you could lay out a mozart sonata in one horizontal line, and diagram the sections, it would be almost identical to your diagram in the second picture. the three parts (left to right) are the exposition, development, and recapitulation. the expo and recap are stable, with the recap being the most stable. the development is harmonically unstable. if the bases of your triangles represent stability (the wider the base, the more stable), then they correspond perfectly with the sections of sonata form. i love it when music and art coincide. gesamtkunstwerk!

i'm mistaken in that the middle triangle is much wider than the first. but since the other sides of the middle triangle are of different lengths, you could say it represents instability...

As always Josh, thanks for the insights from the world of music.

Thought I'd ask you for some info there. I've been wondering about what I think is a Mozart piece, and maybe you can point me to it. I've seen a "tabletop" duet performed in which two musicians (violins in this case) face each other with a piece of music on a "tabletop" between them, and they both play the same page from what to them is the top to the bottom, making a duet of one piece played simultaneously right side up and upside down. It seems like the kind of I'm-a-mathematical-and-musical-genius thing that Mozart would do. Any ideas? I'd love to have a copy of it in my collection of sheet music, buy I can't find it.

i've heard of things like that... i wonder, assuming it is mozart, which is more impressive - whether he did it on purpose or by accident.

Suzanne played the tabletop with Parley... I think. Maybe she still has a copy?

Post a Comment